The Fat Tax in Brazil

What 1960s worldwide hit went on to become the (probably) second-most recorded pop song in history? That’s right, “The Girl From Ipanema,” written by Vinícius de Moraes and Antônio Carlos Jobim:

Tall and tan and young and lovely

The girl from Ipanema goes walking

And when she passes

Each one she passes goes “Ah!”

Additionally, the cool swing and sway of her walk reminds onlookers of a dance called the samba… But what is the use of reminiscing about a sight that has become increasingly rare in Ipanema or anywhere else in Brazil? Sadly, the nation that The New York Times journalist Jack Nicas called “a country known for beach bodies” has changed a lot in the intervening six decades.

Brief digression

Obviously, no one here advocates that overweight and obese people should be mistreated in any way, whether at school, at work, or in the wild. On the other hand, it is a pretty good bet that most obese people would prefer not to be in that situation, which can be uncomfortable in many ways: physically, emotionally, and — as we have especially been looking these days — financially.

One current trend is that all sorts of people pay big bucks in efforts to counteract the unpleasant effects of obesity, their own and others’. But it does not have to be like this. If we could somehow manage to be honest with ourselves and tolerant of others, those two practices would go a long way toward figuring out how to turn this thing around.

Meanwhile, back in Brazil

Still, some might argue that there is such a thing as too much tolerance. For example, in Brazil, obese people are favored with “preferential seats on subways, priority at places like banks and, in some cases, protection from discrimination.”

Note: Many would say that “protection from discrimination” belongs on a different list, because everyone should be protected from discrimination at all times. Everyone has enough problems already, and nobody needs that nonsense.

At any rate, Nicas has described how new laws have “made Brazil the world leader in enshrining protections for the overweight” while an “accelerating movement” has caused the country to become “one of the world’s most accommodating places for people with obesity.” Nicas writes:

[T]he schools are buying bigger desks, the hospitals are purchasing larger beds and M.R.I. machines, and the historic theater downtown is offering wider seats.

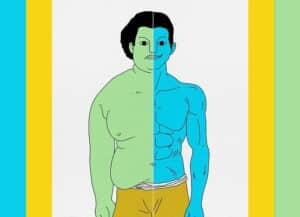

Many citizens resent all this, reasoning that ultimately, sooner or later, one way or another, every customer pays for these seats and desks and beds and machines. Many people favor tolerance in theory but can’t help thinking that perhaps, in practice, there has been a bit too much of it. As Nicas reported in February, “Over the past 20 years, Brazil’s obesity rate has doubled to more than one in four adults.”

Each day when she walks to the sea…

Ipanema is an area of Rio de Janeiro that features a beach. More than a thousand miles north is Recife, another coastal metropolis with great beaches and a population of over four million, and the reputation, Nicas says, of being “one of the fattest cities in Brazil.” He speaks of a public school there that mandated classes on weight prejudice for teachers and students alike. Since the days of the Girl, this whole South American nation has gained weight.

(To be continued…)

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Brazil, Land of the Thong, Embraces Its Heavier Self,” NYTimes.com. 02/27/22

Image by phadoca/Pixabay

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: