WHO’s New Global Guideline for Healthier School Meals

Children spend a large portion of their day at school — learning, eating, growing, and forming lifelong habits. That’s why what they eat in school isn’t just fuel for the day; it’s an investment in future health. The World Health Organization (WHO) recently released a landmark global guideline recommending evidence-based policies to create healthier school food environments, with the goal of shaping healthier generations who thrive both physically and academically.

As we’ve written over and over, across the world, children are facing a “double burden” of malnutrition: rising rates of overweight and obesity, alongside persistent undernutrition. In 2025, an estimated 188 million school-aged children and adolescents — about 1 in 10 — were living with obesity, a figure that now surpasses the number of children who are underweight globally. These trends have long-term implications, increasing the risk of chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease later in life.

Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General, emphasizes the stakes:

The food children eat at school, and the environments that shape what they eat, can have a profound impact on their learning, and lifelong consequences for their health and well-being.

Healthy eating habits begin early — and schools are uniquely positioned to foster them. With an estimated 466 million children receiving school meals globally, schools influence not just nutrition intake but also social norms around food. Yet, until now, there has been limited global guidance on how to ensure these meals truly support healthy diets.

WHO’s whole-school approach

For the first time, the WHO is urging countries to adopt a whole-school approach, ensuring that all foods and beverages provided in schools and available throughout the broader school food environment are nutritious and support healthy dietary habits.

The new guideline highlights actionable recommendations:

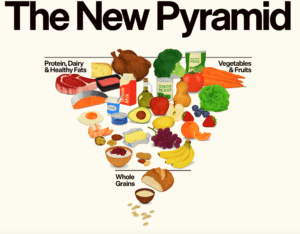

- Establish Healthy Food Standards (Strong Recommendation). Schools should set standards or rules that increase the availability, purchase, and consumption of healthy foods and beverages, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and water. Unhealthy options high in sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats would be limited.

- Use “Nudging” Strategies (Conditional Recommendation). Encourage healthier choices through subtle changes like adjusting the placement and presentation of foods (e.g., putting fruit at eye level) and changing pricing to make healthier options more attractive. These recommendations tap into behavior science to make the healthy choice the easy choice.

Policy is only the first step

Guidelines and standards are essential, but policies must be backed by effective monitoring and enforcement. According to the WHO Global database on the Implementation of Food and Nutrition Action (GIFNA), as of October 2025, 104 member states had policies on healthy school food, and nearly three-quarters included mandatory criteria on school food composition. Only 48 countries had policies restricting the marketing of foods high in sugar, salt, or unhealthy fats.

To develop this guideline, the WHO brought together international experts from diverse disciplines through a transparent, evidence-based process. It now serves as a cornerstone for WHO’s broader initiatives, including efforts to stop the global rise in obesity and promote nutrition-friendly schools. The guideline is designed to be flexible: useful for national ministries of health and education, as well as subnational and city authorities responsible for school food programs.

According to the WHO, it is committed to helping countries translate these recommendations into real change. This includes technical assistance, knowledge-sharing, and collaborations with governments and partners.

To mark the launch, the WHO hosted a global webinar last January, bringing together stakeholders to discuss how to put the guideline into action (you can watch the recording here).

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “WHO urges schools worldwide to promote healthy eating for children,” WHO.com, 1/27/26

Source: “From lunch tray to lifelong health: WHO sets global standards for school meals,” UN.org, 1/27/26

Image by Antoni Shkraba Studio/Pexels

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: