The Coulds and Shoulds of Control

Before we start, don’t miss this important and timely message for parents.

Portion control is all-important, and can be practiced both at home and out in the world, although public venues are more difficult to navigate. For this and other reasons, there is some sentiment for banning “all-you-can-eat” restaurants.

Objections multiply quickly: Economically disadvantaged customers like a place that encourages eating as much as a stomach can hold, and if they slip a few items into a baggie in a pocket, so much the better. This practice might promote obesity, or it might prevent starvation. Besides, someone with a serious eating disorder does not need an all-you-can-eat place to go wild in. That person is quite capable of “sneaking away with strangers’ leftovers” in a regular restaurant.

The contrarians

There are other possible takes on the question. Do these establishments induce overeating? If they do, so what? So does heartbreak, and you can’t outlaw that. As for the argument that an all-you-can-eat format is socially offensive to restrained eaters, let them go eat in some restrained place. These are the thoughts of a great many Americans, along with the freedom arguments. Customers should be allowed to buy any legal substance that someone wants to sell them, and sellers should be allowed to offer any legal product for sale.

Should any ruling body have the power to decree, “There shall be no fixed-price, all-you-can-eat restaurants”? Designating exactly what kinds of eating establishments may exist, and where, could set America’s foot on a slippery slope and lead to such outcomes as the government infringing on business and restraining trade.

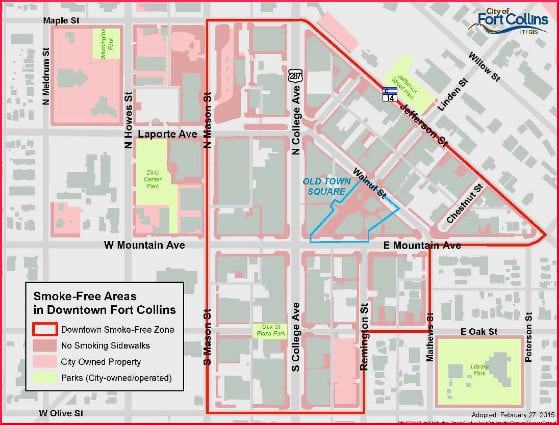

Two U.S. longitudinal studies, conducted in Massachusetts and California, respectively, found that smoking bans in cities were supported by the population over time, and showed that these actions increase the cessation attempts and the number of people who actually quit smoking.

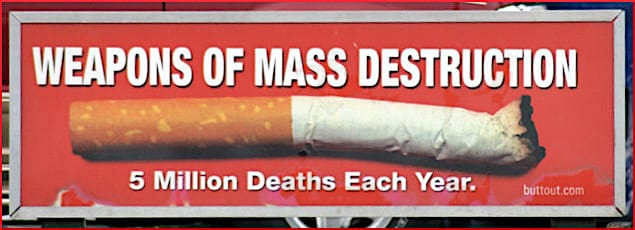

Such research findings encourage hope to spring eternal. Anything that works against smoking, we want to adapt somehow to the exhausting effort to reverse the obesity epidemic. Age restrictions on food are almost non-existent. The struggle to limit the amount and type of advertising aimed at children has been difficult enough. Trying to stop corporations from selling food to minors seems a very quixotic ambition. Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) seemed like a good place to start, and that idea has made progress.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Heart Association recently issued a joint statement calling SSBs a “grave threat” to the health of children. They want stricter chains on advertising and, writes Emma Betuel, to “change the social context in which products are sold.” Betuel writes,

The policy recommendations argue that the government should make it more expensive for companies to market to kids by not allowing them to deduct costs associated with advertising as business operating expenses… They also recommend excise taxes on added sugar that would raise the price of soda. Excise taxes are already used on cigarettes…

Research from Berkeley, CA, is said to find a 52 percent decrease in soda consumption since taxing began. Following the example of nicotine extirpation, they want sodas out of hospitals. The professional organizations want the hospitals to grasp the reins of leadership, as they did with the smoking issue. Hospitals led the way to changed social norms once, and they can do it again.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Lost,” TheSunMagazine.org, June 2017

Source: “Tobacco smoking: From ‘glamour’ to ‘stigma’. A comprehensive review,” Wiley.com, 10/09/15

Source: “In ‘Landmark’ Move, Scientists Say It’s Time to Treat Soda Like Cigarettes,” Inverse.com, 03/26/19

Photo credit: Quinn Dombrowski on Visualhunt/CC BY-SA

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: