Childhood Obesity News is examining the attempts that have been made to decrease smoking, in hopes that the same ideas and tactics might be useful in reducing obesity.

In humans, anything forbidden stirs deep desire. If something is being kept from us, we want it more. That goes double if other people are allowed to have it. Even if no force is involved, people resist being persuaded against some things. The thinking is, “If they won’t let us have it, and want to keep it all for themselves, it must be good.”

This mindset provides a great advantage to the manufacturers and vendors of things that are bad for us, like cigarettes and junk food. Conversely, it imposes a huge disadvantage on the institutions, up to and including the U.S. Government, that want to decrease the availability of things like cigarettes and junk food.

New terminology, old psychology

One of the snares of tobacco has always been FOMO, or Fear of Missing Out. Those who are cool know what FOMO stands for, and those who don’t know, are not cool. Back in the day, if you were a sophisticated, with-it, modern, free-spirited type of person, you knew that LSMFT was short for “Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco.” If you didn’t know, you were missing out, a loser. This kind of mind game goes on all the time, and always has.

For quite a long while, cigarette advertising seemed to be selling an image of substance, respectability, and even dignity. Then it sold an image of equality for women, because just as in every other area of life, women wanted an equal right to kill themselves with cancer. Today, “lifestyle” advertising sells hamburgers and sugar-sweetened beverages to people who are (or want to be) irresponsible, fast-moving, popular — in other words, young.

As the years roll by, advertising copywriters use different details, but the pitch is the same — an appeal to the customer’s FOMO. It works with tobacco and it works with junk food.

The defenders

From the National Institutes for Health:

Tobacco companies have targeted US military personnel since World War I… For example, the military suspended cigarette rations in 1975, but continues to sell untaxed cigarettes in military stores…

In 1986 […] the DOD released Health Promotion Directive 1010.10. This directive established some clean indoor air policies and cessation programs, and prohibited sponsorship of Morale, Welfare and Recreation program activities (e.g., entertainment or athletic events) that identified a tobacco product or brand.

There were free cigarettes, sales and promotions, and all kinds of gimmicky programs ostensibly doing something nice for service members, but basically promoting tobacco products. Historically, even a deserter facing the firing squad was entitled to a last cigarette. Another source concurs:

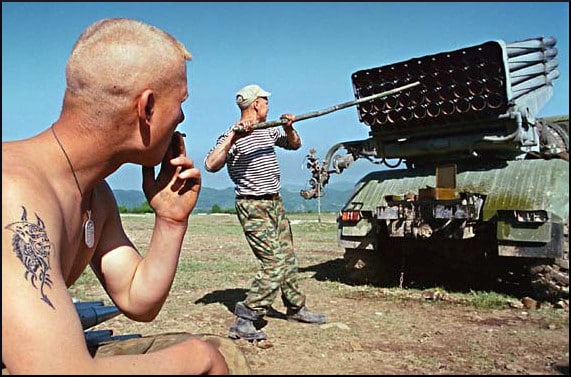

The U.S. military has a culture of tobacco use, which decades of tobacco industry targeting has helped create and support. This culture has driven smoking rates to be significantly higher among service members than the rest of the population and impaired military readiness.

Studies indicate that military recruits are particularly vulnerable to smoking initiation and that smoking rates increase between recruitment and active duty. A 2016 Department of Defense study found that 38 percent of current smokers in the military began smoking after joining.

The Department of Defense has tried some anti-smoking programs, with not much success, especially among Marines who smoke twice as much as the Air Force. Many active duty personnel feel that it would be impossible to both quit smoking, and stay in the military.

Dueling departments

So, two things are going on here. One, the government is at war with itself (and spending a lot of money on both sides) over such conflicts as discouraging smoking, on one hand, and ensuring the prosperity of corporate agriculture. The government’s own NIH website says,

Since Directive 1010.10, numerous stronger tobacco control policies have been proposed by commanders wishing to promote health, but many have been weakened or withdrawn because of pressure from members of Congress representing states in which tobacco is grown.

Also, the question seems unavoidable: “If the U.S. military, the most powerful armed force in the world, can’t stop its own members from engaging in a behavior — then who can?” Of course, the other side of that debate is voiced by soldiers whose objection is, “Who’s kidding who? Uncle Sam says don’t smoke, because it’s bad for me, when at any minute an IED could blow my head off.”

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “‘Everywhere the Soldier Will Be’: Wartime Tobacco Promotion in the US Military,” NIH.gov, September 2009

Source: “Tobacco use in the military,” TruthInitiative.org, 06/12/18

Photo credit: PPSh-41 on Visualhunt/CC BY-SA

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: