Oprah and the Price of Success

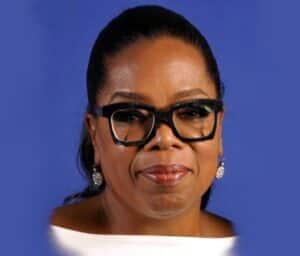

What if, every time you went to the kitchen for a snack, your phone blew up with a few thousand condemnatory messages? By the early 2020s, Oprah Winfrey was accustomed to the extraordinary fact that every ounce of her body had its own crew of both admirers and detractors. Late in 2023, OprahDaily.com articulated the goal of its online presence:

— To bust medical myths and legitimize obesity as a chronic disease that requires intervention like any other condition, rather than a failure of willpower

— To discuss the safety and efficacy of the new weight loss drugs, such as Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro

— To help surface and bridge the inequities and prejudices and remove shame and stigma of living in a larger body.

The website also states that the show aimed “to mainstream the science and psychology” pertinent to the obesity epidemic and to give its diverse and unique audience “all the tools they need to manage their own medical care and mental health.”

Oprah talked about how rough it was to recover from knee surgery while at the same time inevitably gaining pounds, meanwhile still believing the whole enterprise of weight loss depended on her ability to summon willpower. When she heard about the GLP-1 medications, her gut feeling changed and she expressed the determination to try something new, saying,

Whatever your choice is for your body and your weight health, it should be yours to own and not to be shamed about it. I’m just sick of it, and I hope this conversation begins the un-shaming of it.

The world held some solace for her body issues, of course. Unlike most of the population, she could afford to hire custom clothing designers with a genius for draping the generous figure gorgeously. Still, it must be difficult to become comfortable with the knowledge that every time you step up on stage or out in public, millions of eyes are out there ready to judge you, inch by inch. That stuff can mess with your head.

The revolution

Early in 2024 when Oprah announced the end of her association with WeightWatchers, some fans and some chronic critics were upset. People can be very judgmental about the kinds of non-essential drugs they approve of for other people, regardless of whatever pharmaceutical help they themselves may depend on. The GLP-1 products are a sterling example of that impulse. When Oprah revealed that she used that particular remedy, some folks were outraged and others were sorrowfully disappointed — just like when any celebrity turns up in a certain genre of “the news” for any reason.

When Oprah made a decision about how to resolve her lifelong struggle with obesity, fans were already upset because she had discovered something better for her needs, and she was excoriated for realizing what was best for her. It was an honest revelation: “I can’t accept myself if I’m over 200 pounds, because it’s too much work on my heart. It causes high blood pressure for me. It puts me at risk for diabetes…”

That isn’t fat hate, but a simple realization by someone who simply wanted to stay alive and continue to contribute to society by entertaining and educating the public and engaging in philanthropy. By generously sharing her own life experiences, the poor woman became guilty of upholding the standard of the fat-phobic imperative, to be harshly judged by people who were gleeful about what they like to call flip-flopping.

The New York Times described Winfrey as someone who “has spent decades as a dominant figure in the country’s conversations about weight and dieting,” which is one way of saying that perhaps the public should leave the beleaguered woman alone already, and go pick on somebody else.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Oprah Discusses Weight Loss, Obesity, and Ozempic in Her Most Candid Conversation Yet”, OprahDaily.com, 09/20/23

Source: “What Oprah Winfrey said about drugs used for weight loss like Ozempic, Mounjaro,” 09/21/23

Source: “Oprah to Leave Weight Watchers Board,” nytimes.com, 02/29/24

Image by U.S. Govt./Public Domain

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: