More on Childhood Obesity and Antibiotics

This post continues an overview of some investigations into the suspected connection between antibiotics and obesity. In 2016 a ScienceDaily.com piece said,

In the last five years, scientists have made compelling discoveries showing that there may be a connection between the amount and type of bacteria in the intestines and weight gain.

The theory is that antibiotics knock out beneficial bacteria and clear space for harmful ones, although another school of thought proposes that what matters may not be the types of bugs, so much as the balance of power maintained between them.

At any rate, when antibiotics flood the system, massive numbers of our microbial tenants are slaughtered and the result is dysbiosis. It appears that the disturbance “may increase calorie absorption, slow metabolism and cause very low levels of inflammation — all of which appear to trigger a chain reaction that alters the behavior of fat cells.”

PCORnet

The PCORnet Obesity Observational Study is both meta and longitudinal, prenatal and post-birth. It investigates such questions as the effect on the fetus if the mother is prescribed antibiotics while pregnant. If a baby escapes that hazard before being born, the researchers are intensely interested in the first administration of antibiotics to the baby itself, and what happens as a consequence.

The task of PCORnet is to examine the medical records of 42 healthcare systems and figure out what is going on with more than a million and a half children. The activities are coordinated by the Duke Clinical & Translational Science Institute and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute.

One part of the project, in which multiple researchers analyzed data from 35 institutions, concerning more that 362,000 children, concluded:

Antibiotic use at <24 months of age was associated with a slightly higher body weight at 5 years of age.

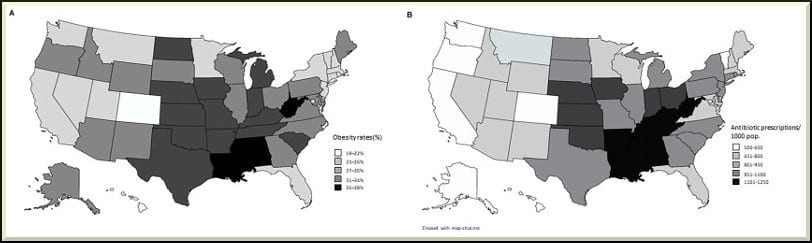

An article published by Frontiers in Pharmacology explains the alarming maps that illustrated yesterday’s post. Data collected in 2014 revealed that for every 1,000 Americans, 835 antibiotic prescriptions were written and filled. When separated by state, and graphically illustrated, the result is a stark admission of undeniable alignment, “a positive and strong correlation, meaning that the higher the use of antibiotics the higher the rate of obesity at that place.”

The authors write,

The scientific community has reached a consensus on the relationship between antibiotics and obesity, showing beyond any doubt that the use of antibiotics causes dysbiosis to varying degrees, especially in children (with less than 3 years of age), which can trigger an increased energy intake from the diet with concomitant increase of weight.

Two more brief notes of confirmation: Clinical Pharmacist published a study of almost 300,000 children who had been given both antibiotics and acid suppressants in the first two years of life. It used data on “241,502 children prescribed an antibiotic, 39,488 children prescribed an H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) and 11,089 children prescribed a proton pump inhibitor (PPI)” and concluded that…

[…] antibiotic exposure was associated with a 26% increased risk of obesity… Combinations of exposure to the three medicine types were associated with increasing risk of obesity, with those exposed to all three having a 42% increased risk.

A recent report from the United Kingdom adds to the sum of knowledge:

Children who receive four or more courses of antibiotics between the ages of two and three years are more likely to be obese by the age of five, a study by Trinity College Dublin has found. The study […] found no statistical increase in weight for children who received fewer than four courses of antibiotics.

One of the implications affecting not only children but adults is that the composition of the microbiome might explain why obesity is such a difficult process to reverse. No matter what a person does or neglects to do regarding weight loss, failure might be inevitable if the obesity is caused by the same cast of characters continuing to reside in the digestive system.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Swelling obesity rates may be tied to childhood antibiotic use,” ScienceDaily.com, 08/30/16

Source: “Early Antibiotic Exposure and Weight Outcomes in Young Children,” AAPPublications.org, December 2018

Source: “Obesity: A New Adverse Effect of Antibiotics?” FrontiersIn.org, 12/03/18

Source: “Early life exposure to antibiotics and acid suppressants increases obesity risk,” Pharmaceutical-Journal.com, 12/18/18

Source: “Childhood obesity linked to courses of antibiotics,” TheTimes.co.uk, 01/20/19

Photo credit: kleuske on Visualhunt/CC BY-SA

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: