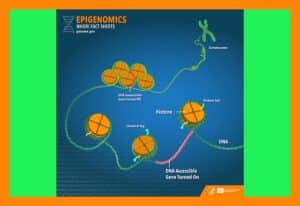

DNA is the instruction book that directs the activities of cells. Epigenetics is the field of knowledge about the heritable changes in the workings of genes, and more importantly, about how their actions can be modified without disturbing the DNA sequence itself.

The epigenome consists of all the genes in the body, plus everything else that influences them for better or worse; and it is malleable. Here is a quotation from the National Human Genome Research Institute:

The epigenome consists of chemical compounds that modify, or mark, the genome in a way that tells it what to do, where to do it, and when to do it. Different cells have different epigenetic marks. These epigenetic marks, which are not part of the DNA itself, can be passed on from cell to cell as cells divide, and from one generation to the next.

Shockingly, over recent decades, it has begun to look as though a person’s genetic makeup does not actually imply inexorable Fate, but resembles something more like a set of very strong suggestions. Even without crazy science-fictional editing tools like CRISPR (clustered interspaced short palindromic repeats), unsatisfactory genes can be outsmarted and over-ruled by the human organism itself.

Moreover, the person who inhabits the body is clueless about the remodeling project. It seems nothing short of miraculous, that thousands of genetic diseases are now seen as potentially fixable by a one-time CRISPR treatment. But all along, Nature has been busy re-arranging the genetic furniture. This quotation is from the Cleveland Clinic:

[The epigenome] changes over time. That can be both good and bad. It’s good in the sense that things like nutritious food, exercise and manageable stress can result in epigenetic changes that can promote health. But other factors like processed foods, smoking and lots of stress can cause epigenetic changes that can harm health.

Various epigenetic changes affect the metabolism, the aging process, brain disorders, inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, the tolerance for neoplasms, and even susceptibility to substance use disorders. It comes as no surprise that these alterations also make a difference around the heritability of obesity. Here are words from the book Genetics and Obesity, by Ekta Tirthani, Mina S. Said, and Anis Rehman:

About 50% of the time, obesity in childhood is carried into adulthood in a phenomenon known as “tracking.” Around 250 genes are now associated with obesity. The FTO gene on chromosome 16 is the most important and carries the highest risk of the obesity phenotype.

So, this is a serious matter, and what are we doing about it? Genetically predisposed obesity can now be treated with “early lifestyle interventions, bariatric surgery, and medications.” Better yet, the discipline of endocrinology “can help treat and control diabetes and other cardiometabolic parameters that cause epigenome changes passed on from generation to generation.”

Out in the world, however, researchers do need to deal with some complications:

In genome-wide association studies done so far, most subjects have European ancestry. However, 47% or the vast majority of patients grappling with the burden of obesity in the United States are of African-American and Hispanic/Latino descent.

Obviously, other countries might also face such problems when attempting to study variegated populations. But the future of the field shows incredible promise in the areas of obesity and metabolic disorders. For instance,

The use of histone deacetylators is now being suggested […] for its use in lifestyle medicine, and research in this field is ongoing. Methylation Quantitative Trait Locus (meQTL) studies are now being used to further epigenetic studies. New Nutri-pharmacogenomic studies are expanding our understanding of how nutrition affects genetics.

The heritability of obesity is easier than many other characteristics to observe and verify with the naked eye. It also is relevant to a very large chunk of the population, and thus likely to attract research grants and generate useful publicity. It should not be a chore to convince the public and the relevant institutions and funding sources of the vital importance of this kind of research, and of the financial support necessary to make it all happen.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “National Human Genome Research Institute,” Genome.gov, undated

Source: “Epigenetics,” ClevelandClinic.org,” undated

Source: “Genetics and Obesity,” NIH.gov, 07/31/23

Image by National Human Genome Research/Public Domain

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: