Last time, Childhood Obesity News considered why kids might lack motivation to take part in a free program that could help them achieve healthy weight; or why, once enrolled in such a program, they might drag their feet and hold back from full participation. Similarly, last month we sighted a headline that read, “Obesity program offers free groceries but lacks participants.” (Maybe people thought it actually was an “obesity” program, when what they really wanted was an “anti-obesity” program.)

Gil Corsey reported for WDRB News on this effort in Louisville, Kentucky, the state that “leads the nation in childhood obesity and preventable death.” The initiative originated with the Shawnee Christian Healthcare childhood obesity study, and is described thus:

The doctor’s office won a $200,000 grant to design a program for the whole family. The program includes free cooking classes, one-on-one workouts, doctor’s visits and even free groceries for six weeks.

Sounds great, right? But Sandy Marshall-King, who deals directly with patients, told the reporter that although 50 or 60 people might register for the program, only a few would show up. This is particularly frustrating because in order to meet the terms of the grant that finances the project, a certain number of people had to sign up. This necessitated going beyond the Shawnee neighborhood and recruiting from the entire city, which is not a bad thing in itself, but it did add a note of discouragement for the health care workers trying to get it off the ground.

Motivation needed

Many solutions for obesity have been suggested and tried, including the ones listed in Slide 99 of Dr. Pretlow’s presentation, “What’s Really Causing the Childhood Obesity Epidemic? What Kids Say.” They include camps and live-in weight-loss centers and programs modeled after substance-dependence programs and family education programs like the Louisville one mentioned above. But all need to start with motivation.

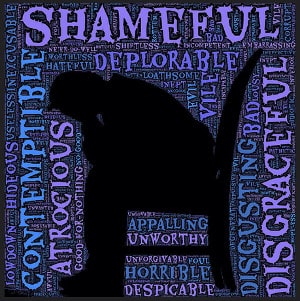

Somebody, preferably the obese patient herself or himself, has to want to do it. We have talked about second-hand motivation in its various guises — nagging, bullying, bribery, threats, etc. What those approaches have in common is that they don’t work, notwithstanding the suggestion by Dr. Callahan of the Hastings Center that maybe more stigmatization is needed.

His theory is based on the fact that social pressure was a very powerful stimulus in his own resolution to leave behind the “reprehensible behavior” of smoking cigarettes. The rationale is that societal disapproval successfully shamed him into giving up that habit, so it might be effective on the habit of overeating. Things are desperate indeed when health professionals, at their wits’ end, are tempted to advance such extreme solutions. Besides, as Dr. Pretlow says:

Education on the effects of smoking doesn’t have very much effect on kids. Kids, particularly teenagers, tend to feel invincible. Motivations such as attracting the opposite sex and being able to wear cool clothes have more effect.

Yes, other motivations have more effect, but too often not enough. However, shaming — even if it appears to work in a few isolated cases — is too risky and damaging to adopt as a policy. Recommendations from the STOP Obesity Alliance include this one:

Address and Reduce Stigma as a Barrier to Improving Health Outcomes –

In fact, stigmatization may postpone and even prevent these individuals from getting treatments that could improve their health. Similarly, providers without effective treatments to offer may avoid discussions about obesity…. Stigma and fear of offending people with overweight and obesity can silence patients and providers and keep them from addressing obesity directly and constructively.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Obesity program offers free groceries but lacks participants,” WDRB.com, 09/02/14

Source: “Policy Recommendations,” TheHill.com, undated

Image by John Hain

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: