One of the interesting outcomes of Let’s Move! was the promise extracted from major national food corporations to remove 1.5 trillion calories from the American diet. Really? How on Earth could a thing like that be measured? Only if the root cause were total crop failure and absolute famine, maybe then such a number could be proposed. Otherwise, proving it will be playground project of the year for some creative statistician. In 2013, a group called Partnership for a Healthier America is supposed to report on how this works out.

There is another organization, called the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, we are told by The Atlantic‘s Marc Ambinder:

Today, the foundation, which includes giant agribusiness concerns like ConAgra […] have agreed to cut a trillion and a half calories from their products by 2012. I’m not quite sure how this is going to be accomplished, nor how the calorie counts break down. Skepticism is warranted, if only because, so far as I can tell, there is no Calorie Measuring Authority, and the science of counting calories is not as exact as one might think.

Armbinder also mentions the enormous amounts spent on lobbying, by the Grocery Manufacturers Association, and adds:

I’d love to see them lobby for, say, tomato and fruit subsidies. More than public events, how these groups interact with Congress matters, because that’s where food policy is set. I should also note that some of these same companies have spent money to convince the public that high fructose corn syrup isn’t as bad as it seems to be.

As Childhood Obesity News has mentioned many times before, the epidemic will not end until food dependency, severe enough to literally be addiction, remains the cause of most obesity. How, exactly, can planting a garden help ameliorate the causes and effects of food addiction?

Doctor Pretlow’s prescription for overweight clients includes the advice to find sources of comfort that are not food, such as pets, volunteer work, books, hobbies, and clubs. Growing a garden is a solid hobby, and if you give some of the food away, it’s volunteer work, too. And a person has to eat something. If the program is to abstain from the most addictive possibilities, like hyperpalatable junk food, something else needs to be eaten instead, and it might as well be fresh veggies from a family’s own kitchen garden.

Kids and grownups who are out digging in a garden are probably not subjecting themselves at those moments to any television ads urging them to eat chocolate-covered bacon. That’s a plus. There is a lot to be said for an emphasis, within a family, on healthful eating. If family members can spend time in the kitchen together, developing togetherness and bonding, so much the better. When a family is close, there are not so many emotional gaps to be filled by deviant eating patterns. Kids might develop other interests besides sitting around drooling over TV food ads.

And doing something is better than doing nothing. Currently, thanks to the First Lady and Let’s Move!, the national focus is on childhood obesity. As Dr. Pretlow says:

The challenge is how to tap into the energy of these initiatives. There are a multitude of these healthy eating, healthy exercise efforts to combat childhood obesity. Some do help, but I feel that they divert attention away from the underlying comfort-eating/dependence/addiction cause. Each program should thus be examined through the psychological food dependence — addiction lens to see if it helps the underlying comfort-eating/dependence/addiction problem.

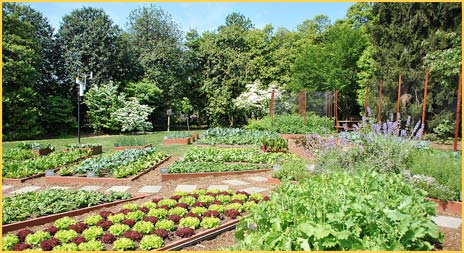

According to White House lore, Mrs. Obama’s Kitchen Garden was started in 2009 for less than $200. Which is more than a lot of families have for such a project. The First Family also has a huge staff to take care of things. But really, almost anybody could potentially grow something. Even in a single room, a person can grow sprouts. From there, who knows where a person might be inspired to venture? What can it hurt to try?

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Cutting 1.5 Trillion … Calories,” The Atlantic, 05/17/10

Image by angela n.

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: