Kids have a natural talent for identifying baloney. They love to compare what parents say on Monday to what they say (or do!) on Tuesday, and if it doesn’t match up, look out! The average child possesses a highly developed critical sense that is constantly on the alert for adult self-contradiction, and especially for adult hypocrisy. It just might be possible to divert some of that talent into a useful channel — useful to resist childhood obesity, that is.

It’s good for a parent to help a child develop a baloney detector, which is always a primary survival tool throughout life. Of course, in order to do this, parents first have to be pretty clear-headed themselves, and apparently not all of us are. This discouraging story by Gerry Pugliese is called “Parents Buy Bad Food If Athletes Endorse It.” He talks about a study and its methodology:

The scientists presented the products in a variety of ways, either a plain package with nutrition facts, a package also including nutritional information and nutrition claims – such as ‘High in Calcium’ — or a package with a celebrity athlete endorsement, saying something like ‘I love this high fiber cereal.’

Less than half of the participants read the nutrition facts on the product’s label. They were all parents of kids ages between five and 12, and they didn’t want to read the fine print, although they did go for the “nutrition claim” if it was printed on the front. Worse, they were impressed by the endorsements of celebrity sports stars. It’s almost as if people don’t understand that athletes are paid millions to go on record saying they can’t live without some particular breakfast cereal. It’s all a great, big, nose-growing, pants-on-fire L-I-E.

Because of the types of fiction and games they are exposed to, in which the hero or heroine saves the Earth and all its people from some juggernaut of doom, kids are familiar with gigantic plots and worldwide conspiracies. They just might be willing to fight against the Junk Food Conspiracy, the huge plot to get everybody hooked on stuff that not only isn’t good for us, but is actually very bad for us. Make a game of spotting advertisements that appeal to the inner addict that unfortunately seems to inhabit most of us.

When confronted by advertising, savvy parents can make a game of spotting ridiculous claims in commercials and calling the bluff of hidden agendas. A grownup who pays attention can help a child deconstruct commercial messages and strip them down to reveal them as blatant snow jobs. Ads that urge us to satisfy our cravings are, of course, reinforcing addictive behaviors. When an ad tells us how much we deserve this goodie, because of what a wonderful person we are, or how hard-working, or how deprived, it’s a transparent ploy. An ad that tries to convince us that we are entitled to the fantastic reward of chowing down on its product, is a con job.

There are several basic varieties of advertisement to work with. Bring kids into the game of identifying them. “Look at that! Those people are saying that if a mommy doesn’t get that kind of cereal, she doesn’t love her little boy. Isn’t that the silliest thing you ever heard! Here’s what a mommy does when she loves her little boy.” (Mom picks up child and dances around the room.)

When kids get a little older, you can act out some real-life math to illustrate a point made by Sarah Hughes, in her reflection on the work of Dr. David Kessler, one of the leaders in the childhood obesity field. Hughes says,

We are seduced by the packaging telling us we’re getting an extra 15 per cent for free, yet Kessler tells us most of the time that 15 per cent is something synthetic, designed to ensure more profit heading the food company’s way.

Say, there’s a bag of cookies sitting around your kitchen, whose package proudly announces, “Now! 10% MORE!” Lay down 10 cookies on the table and a little pile of something that’s the same size as a cookie — like styrofoam or dryer lint. Help your kid understand that this is how advertisers lie. You may be getting 10% more — but 10% more of what?

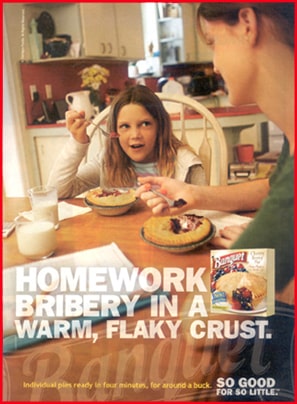

It depends on the child, of course, but a parent could try explaining why, for instance, the magazine advertisement shown on this page is such a disgrace to humanity. Now is a good time to start demonstrating that extrinsic rewards are not always available or advisable.

How would it sound if you said this to a child? “It’s so wonderful that you’re doing your homework. Plus, I love you. So, here is something that will make you fat and maybe even pimply, and the other kids will laugh at you, and you won’t be able to fit into the seat at the movies or the rides at the theme park. Also, you might have to settle for some loser of a boyfriend, and probably get some horrible grownup disease 40 years too early. So, eat up, sweetheart!” Maybe you can get the kid to laugh and settle for a carrot instead.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Parents Buy Bad Food If Athletes Endorse It,” Diet-Blog.com, 02/20/11

Source: “Why one cake is never enough: Addictive additives in food MAKE us eat more,” Daily Mail, 08/03/09

Magazine advertisement is used under Fair Use: Reporting.

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests:

3 Responses

I am glad that no matter WHAT the media promoted, or what food pyramid was endorsed, I pretty much followed what my parents used as the food model when I was growing up. It included a mix of grains and proteins and fruits and veggies, and things like Coke were a once a week treat and I had to split the bottle with my brother. Today, as grown adults, they are better than I am on nutrition, and make most meals from scratch with whole food ingredients. Too bad the teevee messed up a lot of my generation, encouraging us to want things.

When I was a kid, there might be soda pop around at Christmas. Or if we went to the drive-in movie, my sister and me in the back seat in pajamas, with a paper grocery bag full of popcorn and a soda pop.

But even growing up in a soda-pop desert, I managed to have the world’s worst mouthful of teeth. How did that happen?