Where Do Meaningful Metrics Come From?

While spontaneity is admirable, agreement upon standards also has its very large and important place. Experts are trying to resolve important issues, like whether food deserts exist, and if they do, what should be done about them. When these consultants make decisions and recommendations, the people have to follow rules they perhaps don’t care for, and watch their tax money pay for unconventional and seemingly frivolous projects.

In the metaphysical realm, the law of unintended consequences is strict and cranky. Because this is so, when legislation is enacted on any level, there is (or should be) strong incentive to get it right. Part of that is getting the right information, and another part is knowing what to do with it.

GIS and other tools

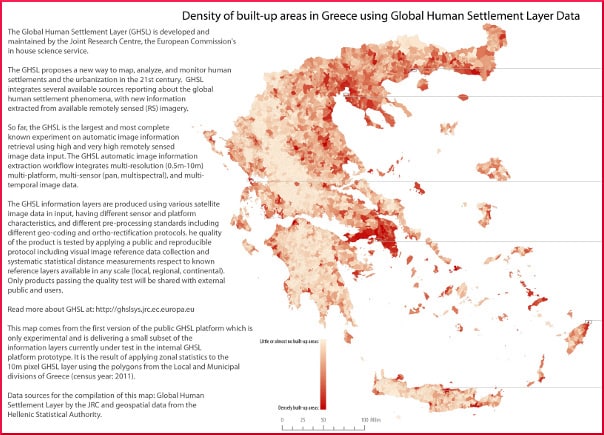

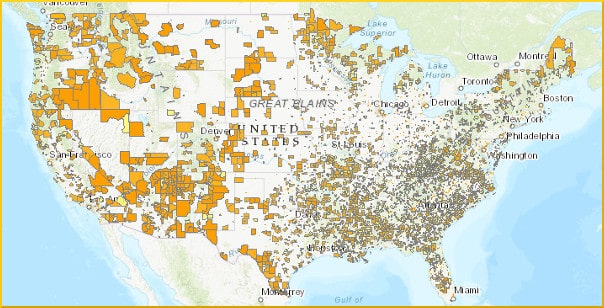

In many fields of human endeavor, fusion produces impressive results. The geographic information system (GIS) is a melding of data and geography. We like having a mental picture to relate to, and GIS mapping will generate one or many, depending on requirements. The technology can display details about demographic, political, and economic factors in an easily comprehensible form.

GIS techniques can make maps where color intensity tells the tale, or convey information in two dimensions that look like three, or even create three-dimensional artifacts. It might make a picture that looks like a mountain range, where the highest peak represents the forest with the most elves — or the state of the Union with the most obese children under the age of 5.

GIS provides researchers with a framework in which to compile and manipulate data, with room for analysis of patterns, situations, and relationships, and for communication about them. It handles layers of information and lends the viewer a key to visual interpretation. As one source puts it,

GIS technology applies geographic science with tools for understanding and collaboration. It helps people reach a common goal: to gain actionable intelligence from all types of data.

Some matters are more geography-driven than others. The food desert dilemma is unquestionably crucially aligned with geography. Planners want to know the proven utility of encouraging more farmers markets, virtual grocery stores, and Corner Store programs. Will these actions ameliorate the health effects of bad food? We learn that “Information derived from GIS mapping is the predominant means of determining food availability.” So it is pretty important.

“Redefining the Food Desert” dissects the example of Bridgeport, CT, where food access was measured by enlisting both computer-based GIS mapping and on-the-ground direct observations of retail inventories. It doesn’t seem like they talked very much with area residents. The report even mentions this omission:

While the GIS output indicates generalized food accessibility issues, supplementation by survey data reduces the geographic extent of the food desert problem.

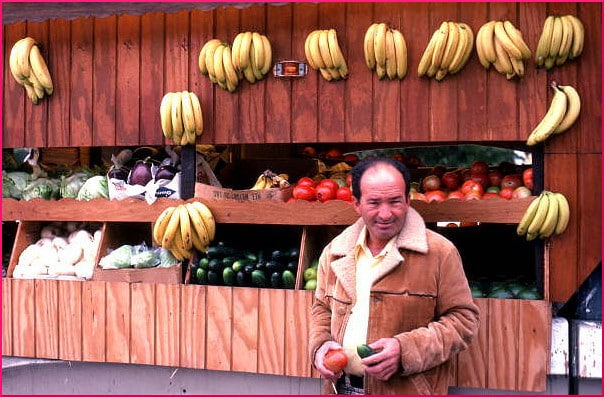

In this context, “supplementation by survey data” means asking the people who live there about the reality of their daily transactions. In some quarters, it is suspected that, in the quest to identify food deserts and more importantly, to do something about them, crucial aspects may be missed. Maybe people are not listened to enough, or questioned appropriately. “Does your local mom-and-pop grocer carry veggies?” is a different question from “Are they fresh and do you ever buy them?”

One acknowledged drawback of GIS mapping is its “inability to determine what products are actually available to residents in neighborhoods not served by a major grocery store,” which seems like a pretty serious methodological flaw. The glaring lesson here is that even the most elegantly executed map doesn’t mean zip if, at ground level, it measures the wrong things or depends on skewed data to get answers. Whatever its shortcomings, GIS mapping itself is not to blame, because the results depend on the information that is fed into it by humans, who are far from perfect.

P.S.

This is a good opportunity to recall that in Dr. Pretlow’s book, Overweight: What Kids Say, the Introduction credits the “anonymous, amazingly outspoken, bulletin board and chat room messages” written by “thousands of different overweight kids” and received by the Weigh2Rock website. The book was inspired by the idea of listening to the people who are actually affected by the phenomenon it describes.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “What is GIS?,” esri.com

Source: “Redefining the Food Desert: Combining Computer-Based GIS with Direct Observation To Measure Food Access,” ResearchGate.net, Dec 2014

Photo credit: TheVRChris on Visualhunt.com/CC BY-SA

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: