The Non-Equivalency of Smoking and Overeating

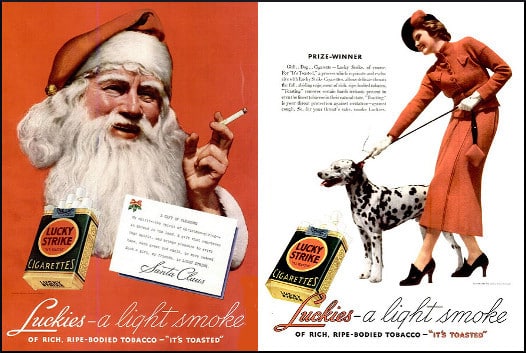

In the national effort to reduce smoking, stigmatization plays an important role. But a nicotine habit, even an addiction, is qualitatively different from a state of being, like obesity. Smoking is something a person does, rather than something they are. Sure, somebody who smokes is a smoker, but that is seen as an extra thing added on, like aftermarket wheel rims, instead of an essential component of personhood.

A smoker is criticized for something she does; an obese person is taken down for something she is, which is a different proposition. Expecting someone to stop doing something is quite different from asking a person to stop being something. It is also the reason why stigmatization is unable to play as large a role in stemming the obesity epidemic as it does in slowing down the rate of smoking.

Crucial differences

Someone who is shamed into quitting tobacco is congratulated and celebrated, and the love is relatively easy to earn. All this individual has to do is continue not smoking, and with the extra advantage of being able to set up a lifestyle that avoids contact with tobacco and with other smokers. A person who is shamed into losing weight does not collect the same reward of brownie points, but at the same time, faces a much harder road. No one can shift to a lifestyle that excludes food and people who eat.

Smoking cessation benefits others in tangible, identifiable ways — releasing less pollution into the air and fewer cigarette butts onto the streets. It is more difficult to point to environmental benefits from weight loss, because the fat person himself is considered to be the blot on the landscape.

Smoking cessation has emotional, tangible benefits for others. For instance, it helps the quitter live longer, to care for and be available to family members, which is a help to them. Many ex-smokers are appreciated for that in an ongoing fashion, like yearly no-smoking “birthdays.” Weight loss achieves those same ends, yet, for some reason, it is more difficult to grant weight losers the acclaim they deserve while moving forward through life.

Essential differences

Although social opprobrium has been partly responsible for the decrease of smoking, there is a deep-seated reason why it can’t work the same way against the obesity epidemic. There is an obvious and distinctive difference between being shamed for smoking and being shamed over obesity. Generally, the people shamed for smoking are grownups. A child smoker is unlikely to be shamed, because if a child is smoking at all, it’s likely in a family and a culture where kids smoking is no big deal.

A grownup smoker has a history of life experience, and may have faced criticism and opposition for other choices. A certain amount of hard shell has built up around that person’s psyche. An adult probably has a job, which adds a layer of self-justification, as in, “Hey, I’m making a good salary. If I want to spend my money on cigarettes, how is that your business?”

A 5-year-old “fatty,” mercilessly teased by peers and picked on by family members, is a different case. That little self is barely formed, vulnerable, soft, and defenseless. Relentless negativity finds fertile ground in which to cultivate depression, self-loathing, and a body image that might be even worse than reality. In this morass of ugliness, problems like exercise avoidance and maladaptive eating patterns are unlikely to be addressed. That person grows up accumulating additional bad experiences related to obesity.

As time goes on, the person carries around more and more emotional baggage, along with a slicker ability to rationalize the very behaviors that cause the problem. And no matter how much pain has built up, and regardless of how much more is added to the pile, a thick skin may also be growing — a coating of indifference that looks like a bad attitude, one that says, “If you can’t love me as I am, just go to hell.”

Fat-shaming is worse than wrong — it’s useless

The message for normal-weight people is, good luck trying to shame an obese grownup. She has heard it all before, and learned to “stuff” that pain along with everything else. He has had a lifetime to prepare all the necessary rationalizations, and to develop all the reactive hostility needed to completely ignore the shamer.

The number of people who have lost significant weight to please another human is vanishingly small. Sure, we should avoid fat-shaming because it is unkind and hurtful. But an even more excellent reason is the ruthlessly pragmatic one — it doesn’t work.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Photo credit: Julie Facine on Visualhunt/CC BY-SA

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: