A Walk Down Memory Lane With Tobacco

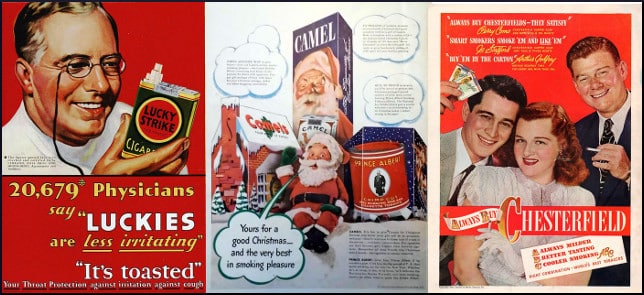

Christopher Gildemeister of the Parents Television Council takes readers back to 1964 when the U.S. Surgeon General released the landmark “Report on Smoking and Health” that “caused a massive shift in American understanding of, and tolerance for, smoking.”

In those days, broadcast entertainment consisted of three TV networks, and radio, so any voice projected into the public consciousness through those channels would pretty much be guaranteed an audience, and didn’t advertisers know it! Some people were fed up with cigarette commercials, but couldn’t figure out how to get rid of the plague, so instead they tried to counter them with more commercials, of the anti-smoking genre.

The journalist notes other historical steps:

1967, the Federal Communications Commission required television stations to air anti-smoking advertisements at no cost to the organizations providing them. In 1970, Congress had passed the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act, which banned the advertising of cigarettes on television and radio. The last cigarette commercial on television aired on January 1, 1971.

So the manufacturers quietly slunk away and licked their wounds. April Fool! No, instead they paid filmmakers to insert depictions of their products into movies. The character is going to smoke anyway, right? And movies are expensive to make, so why not let the cinematic artwork help to pay for itself by showing a brand name for a second or two? Such was the thinking, anyway.

In November of 1998, the Attorneys General of 46 states got together with the tobacco sellers to ratify the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA), which put an end to paid product placement, as the transaction is known, in movies or TV shows. Of course, some people are never satisfied, and wanted to put an end not only to payola, but to unpaid brand depiction. Others dreamed of complete abolition of any smoking whatsoever, even if the depiction was non-branded.

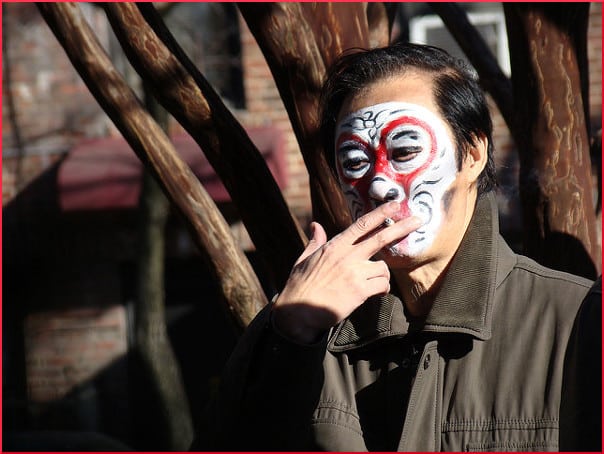

Researchers looked at more than 2,000 “top box office hits” released over a period of more than 20 years (1988-2011). Three metrics were involved:

[…] the proportion of movies with smoking, and among movies with any smoking, the number of scenes in which characters smoked, and the average length of a smoking scene.

Post the signing of the MSA, they found “an exponential decline in tobacco brand appearances in Hollywood movies.” This is hedged in careful language like “speculative,” “associated with,” and “circumstantial evidence.” They also found downward trends “in the proportion of movies with any smoking and the number of character smoking scenes in movies with smoking. One quotation is,

This study’s correlational data suggest that restricting payments for tobacco product placement coincided with profound changes in the duration of smoking depictions in movies.

In that statement alone are three equivocal terms — “correlational,” “suggest,” and “coincided with.” So it might be that the change was more wishful thinking than anything else, which is why this post will be continued.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “TV Stubs Out Smoking,” ParentsTV.org, 2008

Source: “Did limits on payments for tobacco placements in US movies affect how movies are made?,” BMJ.com, 2015

Photo credit (left to right): Phil Wolff, Joe Haupt, Alden Jewell on Visualhunt/CC BY-SA

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: