What Is Parenting Style?

For a child, the world has two forms. One part is outside, where obesity hazards exist that are shared with others, like crummy neighborhoods with no play space, and low availability of healthful produce.

That larger world affects babies, but they don’t know it yet. The world they are mainly concerned with, and influenced by, is the one within the walls known as home. It is populated by big people — everybody is bigger, stronger, and more capable than a baby — and the biggest ones are running the show.

Childhood Obesity News has discussed quite a few of what are known as early-life risk factors, of which more are identified every year — or, if not identified, at least proposed as serious candidates for investigation.

A 2013 report from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln said,

Risk factors often do not occur in isolation. Further, few studies have tried to capture the complete picture of childhood obesity risk factors… It is well accepted that there is no single cause of childhood obesity, but coactions at multiple levels (e.g., genetic, cellular, physiological, psychological, social, and cultural) determine outcomes.

The truth of this has been confirmed over and over again. Multifactorialism is inescapable reality. Each suspected factor calls for extensive exploration. Society has to know which ones pose the greatest danger, and, consequently, which ones should be allotted the greater share of resources.

The challenge is to recognize the multifactorial nature of the child obesity epidemic, and yet identify and rank the individual factors with due diligence. One of those factors is parenting style.

What is it?

Many thinkers have pointed out that parenting style is not only the decisions that are made, but also, in some cases, the decision not to decide. Canadian researchers wanted to know “how parenting styles and the broader social environment combine” to affect the obesity risk of preschool and school-age children. To this end, they defined four styles or modes:

Authoritative — both responsive and demanding

Authoritarian — not responsive but demanding

Permissive — responsive but not demanding

Negligent — neither responsive nor demanding

Some of the better known childhood obesity risk factors are parental obesity, breastfeeding duration, childhood television use, and nighttime sleep duration. How do those common traits match up with the parenting style categories? Things might have been different in the past, but these days, any kind of parent can be obese.

It seems as if breastfeeding duration would have a better chance among permissive and even negligent parents, than with the other two kinds. Permissive and negligent parents definitely result in more kiddie screen time and shorter sleep duration.

Does this mean that the authoritarian or even the authoritative styles are better for kids? Not necessarily.

(To be continued…)

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Risk Factors for Overweight/Obesity in Preschool Children: An Ecological Approach,” UNL.edu, October 2013

Source: “Childhood obesity is linked to poverty and parenting style,” Concordia.ca, 11/10/15

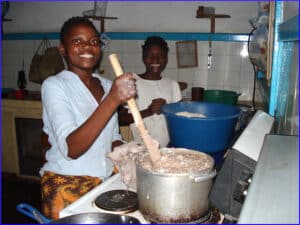

Photo credit: shrapnel1 on Visualhunt/CC BY-NC-ND

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: