Obesity Villains Examined

Over the years, Childhood Obesity News has pointed the finger at numerous villains who share varying degrees of culpability for obesity. Many of these have been the same entities mentioned in “Ten putative contributors to the obesity epidemic.”

Its roster of 22 authors included Dr. Joe C. Eisenmann who by now has accumulated 30 years of experience as a coach, professor, researcher, educator, applied sport scientist, and strength and conditioning coach. Children’s health, fitness, and athletic development are his missions, and “tested, trained, energized” are his watchwords.

For his own website, Dr. Eisenmann has written that,

The benefits of exercise on the child and teenage brain include:

– improved concentration, cognition, memory and academic performance

– better self-esteem

– stress reduction

– decreased likelihood of mental health issues like anxiety and depression

– decreased severity of ADHD symptoms and autism spectrum disorder

An immature, growing brain needs to assemble itself from a lot of moving parts, and research has shown that taking into account the needs of both structure and function, physical exercise plays an enormous part in helping it to do so.

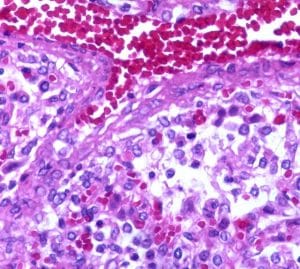

Returning to the subject of obesity villains, what newsworthy candidates did the multi-author project mention? Regarding epigenetics, there is said to be basic in vitro evidence, animal evidence, and epidemiological evidence that the area is worth scrutinizing:

Animal models and human data illustrate that dysregulation of epigenetic processes can cause obesity. Recent molecular studies provide an additional link by showing that genes critical to energy balance are regulated by epigenetic mechanisms…

If the intrauterine environment of an obese woman induces developmental adaptations in her developing fetus that then predispose her offspring to obesity, feed-forward transgenerational amplification of obesity could result.

The subheading “Intrauterine and intergenerational effects” is ticked for animal evidence, ecological correlation evidence, and epidemiological evidence. Speaking of bariatric surgery patients, the report says, “Children born after maternal weight loss have a lower risk for obesity than do their siblings born before maternal weight loss.” This leads to an area called metabolic imprinting, suggesting that body weight could be regulated by epigenetic means.

Another factor discussed here before is “assortative mating,” the tendency of humans to become intimately involved with others who have similar characteristics. But they also become involved with others who have very different characteristics, and lust has always been like that. Also, it pretty much guarantees that if two obese people have a child, that child is likely to be obese.

It also implies that an overweight person is more likely to ask an overweight person on a date, having learned from experience that potential partners of normal weight don’t really consider themselves as potential partners. According to folk wisdom, it takes a lot of personality to overcome a serious weight differential. Still, as the paper indicates,

The consequences of assortative mating are complex and dependent on the “genetic architecture” of a particular trait. Given that obesity is a complex polygenic trait, models of assortative mating are quite complex.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Ten putative contributors to the obesity epidemic,” ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, November 2009

Source: “New Year. New Platform. New Logo,” JoeEisenmann.substack.com, 01/03/23

Source: “Exercise and Brain Health for Young People: Another Puzzle Piece to Achieving Optimal Well-Being,” Substack.com, 10/29/23

Image by Loco Steve/CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: